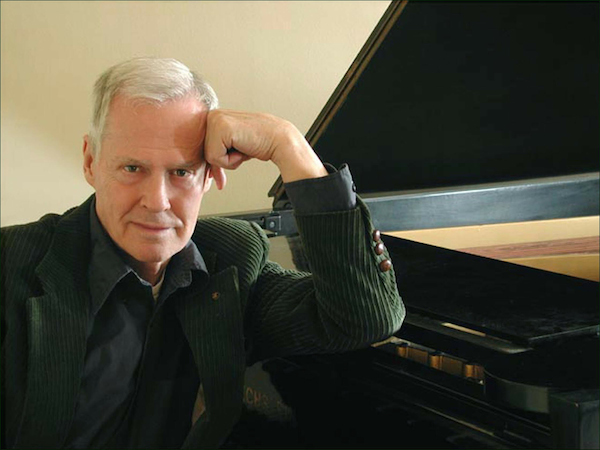

Ned Rorem (Photo © Christian Steiner)

Last week, on Oct. 23, Ned Rorem celebrated his 91st birthday. I studied with Ned at Curtis from 1993-97. It was an experience that one could never forget, and it shaped me forever.

While I’m a few days late in getting this out into the world, I thought I’d share a little something I put together for him a few years ago. In 2008, in preparation for Ned’s 85th birthday, Daron Hagen solicited some brief reminiscences and tributes for a Festschrift he was compiling. I gleefully contributed the following words:

To Ned Rorem on His Eighty-fifth Birthday, 23 October 2008

In May of 1993, my father, mother, future sister-in-law, and I traveled from our hometown of Puyallup, Wash. to West Point, N.Y. to attend my brother Carl’s graduation from the United States Military Academy. (My mother’s parents made the trek up from Florida for the occasion as well.) One of that long weekend’s festivities was a formal dance, to which I escorted my mother, while my father hung back to take his in-laws out to dinner.

My grandfather, Wallace Franks, came from solid working-class Ohio stock, though he himself was a music educator who had studied composition under Sowerby at Northwestern (and who at one time was close to the likes of no less a luminary than Percy Grainger). As I was about to commence my studies at the Curtis Institute of Music later that same summer, my grandfather took it upon himself to advise my unsuspecting dad that night just exactly what I was in store for. . .

“John, I want to tell you something,” he said to my father.

“Wally! No!” my grandmother pleaded.

“Joanne, let me speak!”

“No, Wally!”

“John, do you know that Ned Rorem is a homosexual?”

My father merely shook his head, saying, “Oh, Dad. Of course we know!”

Thus my grandfather attempted to prepare me and my family for the next four years of my musical upbringing.

The fact is, nothing could have prepared me for my first lesson. Luckily, one of us three students of Ned’s was returning to his second year at Curtis—Jonathan Holland. (The other—Luis Prado—like me was a first-year.) Jonathan let me in on the fact that, at Curtis, we dress up for our lessons. Therefore, I was at least properly attired for the occasion. I donned my best coat and tie, and waited upstairs in one of Curtis’s plushly appointed studios for my first lesson with Ned.

It wasn’t that Ned was harsh, so much. It was more his frankness, his honesty. I remember him taking me to task for my meager yeoman offerings. The brightest moment in the lesson was when he pointed to a line (in an inexpert quartet for violin, two violas, and cello) and claimed, “I wrote that same tune in a piece of mine.” That, at least, meant one bar of the music was beyond reproach.

Every lesson from that point on took place in Ned and Jim Holmes’s apartment on the Upper West Side. I kept a sort of on-and-off journal (still do) and wrote a couple of entries about those lessons. Here is one written when I was 19, during my second year at Curtis:

12 November 1994

Rorem’s apartment & train home from NYCHaving just finished my portion of our lesson (Jonathan Holland, Luis Prado, myself [sic]) I have decided to catalogue the events while they are fresh in my mind. I’m sitting at the dinner table, with Jonathan and Mr. Rorem in the next room at the piano. The table top is like a still life painting; bowls of fruit, half-drunk cups of coffee, empty yogurt containers, half-eaten brie[,] and a heel of rye bread on a cutting board. (Not to mention a box of just opened Entenmann’s Banana Crunch Cake. I think I’ll indulge. . .) We arrived at 18 W 70th St. Apt. #6B at 12:30pm. We sat down at the deep red painted table for [a] lunch of quiche, yogurt, fruit, brie/bread, and red “mystery” juice. I went briefly to the restroom to wash my hands and when I returned, Jonathan and Luis were feebly attempting to answer one of Rorem’s little quizzes: “Name ten living American authors.” They had managed two. Thank God I had missed that embarrassment. (I would have managed zero, I’m terribly under read.) Rorem went on to say that no one knows anything related to culture or art these days, except his extremely bright Curtis students. (His secret is safe with me.) We discussed various topics, or we listened to him speak, about women composers and other things related to composition. At one point he said, “One can’t judge a piece, whether it’s good or bad, only if it works or not.” He’s right. (Of course he’s right.) Luis went first today because he had to leave early. Rorem called us all in to look at Schumann’s Faschingsschwank aus Wien which he would like us to orchestrate. We agreed wholeheartedly. I think I will benefit from the assignment.

When it was my turn to go I showed him my orchestra Theme & Variations. He noticed right away the two notes I had changed in the theme. The two notes which would “make or break the whole piece” (his words). He approved. He also approved of the new cello line. He thought that perhaps the cl. & ob. should switch roles after the third time through. It would be more “professional” in his eyes. He did criticize some doublings (hrn. & bsn.) at one point. In fact he disliked all doublings, as I suspected. I tried to explain to him my ideas of the form of the piece as best I could. He probably understood. I also expressed my anxiety about the orchestration of the whole thing in general, and mentioned Daphnis as a model for me. Meaning that I would like to achieve the architectural effects of the long, sustained orchestral crescendo. Rorem suggested I look at Pictures at an Exhibition (Ravel’s orchestration). In fact he lent me his copy of the score. (I’m flattered.) Although it wasn’t a lot of music that I brought him, he didn’t chide me. He mentioned at the end of the lesson (after Jonathan had had his private session) that neither of us had very much music but that he thought what we did bring was good. I think he likes my piece so far; he was whistling the theme to himself at one point in the lesson. Rorem briefly mentioned a piece by Rzewski call The People United Will Never Be Defeated! He mentioned it only for the fact that it was political. (Something he believes music to be incapable of expressing. He’s right. [Of course he’s right.])

A couple years later, I wrote this brief entry late one night in Philadelphia:

Here’s an example of the effect Ned has had on me: every word I’ve written in this tiny tome since I’ve been at Curtis (hard to believe I graduate two weeks from tomorrow!) I feel has to live up to his scrutiny, even though he’ll never read any of it. It’s as if his colossal blue pen is looming just above my head, ready to dash its royal blood all over these poor pages.

Ah, the way time doesn’t fly when you’re young. Those four years felt like a lifetime. I remember distinctly the shock of no longer being a Curtis student, of no longer being Ned’s student. He was the closest thing I had to a musical father. (After all, what are we students if not the progeny of our teachers?) Who would keep me honest as a composer? Even if, after four years, I felt I could predict what he would say about my music in a lesson, knew I had practiced restraint in all manners orchestrational and harmonic, had wrung out all extravagances and rendered all melodic parts lean and clean, he would still find something. (There’s always a better bass line.) I couldn’t fathom being able to do so for myself.

At the same time, by the end of my studies I yearned for something different. I wanted a teacher who would let me use a marimba, if I wanted one. I wanted someone who would let me bathe in a chord if I (and that chord) deserved a bath. I was hoping for someone who would let that section go on too long, if I didn’t feel like being succinct.

And yet, now, on the other side of things, am I so surprised at whose voice I hear echoing in my ears, even as my own lips form the words? When I see that octave doubling in my students’ music, I suppose I see now what Ned saw in mine. But it’s not just his admonitions that stick with me. It’s his music, too. In fact, they are Ned’s scores that I reach for most often when I need to illustrate a point. I go for the works that are dear to me – the String Symphony, Bright Music, Spring Music, the Fourth Quartet, Sunday Morning, the flute trio, Evidence of Things Not Seen, not to mention a whole host of other songs. These are the pieces, too, that I listen to for pleasure. If Ned is no longer a weekly presence in my life to keep me honest, his music certainly is.

If I hope for anything to come from the writing of this brief remembrance, it’s that Ned himself realizes just how important his music is to this former student. I wish him to know how vital his instruction remains; that he continues to instruct and inspire.

Dear Ned, I wish you all warmth and happiness on your eighty-fifth birthday. You have my utmost devotion and affection.

With love,

Daniel Ott

What else is there to say except that, six years on, the sentiment has not diminished? As an added tribute, I present the youthful Piano Sonata No. 1 (III. Toccata), as played by Thomas Lanners, from the ever-youthful Ned: