In just over one week from this precise moment†, my good friends Alex Freeman and Mathew Fuerst, together with the Amernet String Quartet, will present the second-ever program of our works on a concert at Merkin Hall on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. It’s going to be an exciting program, and we are delighted by the venue—I boldly predict that nothing (and I mean NOTHING) could possibly stand in the way of it all going as smoothly as humanly possible.

The Amernet Quartet (l-r: Jason Calloway, Michael Klotz, Misha Vitenson, Tomas Kotik):

A few days ago, I had the thought that, since I know these two composers so well, and since every time we’re together we always talk some serious shop, wouldn’t it be great to invite them to talk about their works? After all, I am always being asked questions about what it’s like to compose.

Sometimes those questions come from people with no musical background (“Do you really hear music in your HEAD?”), and sometimes they come from people who know composers all too well (“You’re STILL not done???”)

But I have found that rarely does the audience (or even the performers, for that matter) get to hear about composing from the insider’s point of view. There’s a lot of superficial stuff—”I was inspired by this or that”—but not a lot of “inside baseball” shop-talk. So I asked Alex and Matt to contribute to this post, and I’m going to try to do the same about one of my quartets.

* * *

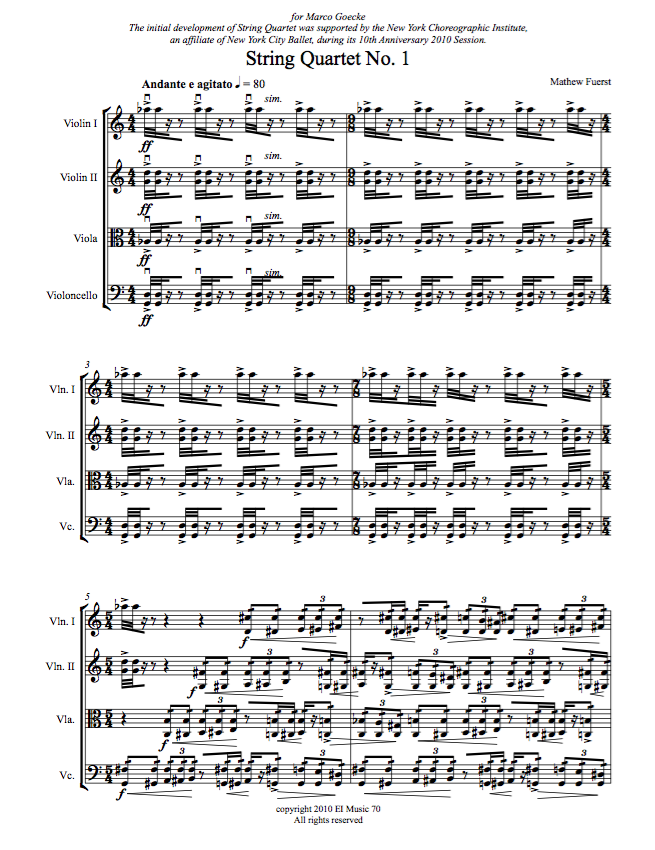

Matt has written two quartets, and both are on this program. He wrote the following about them:

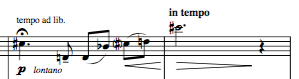

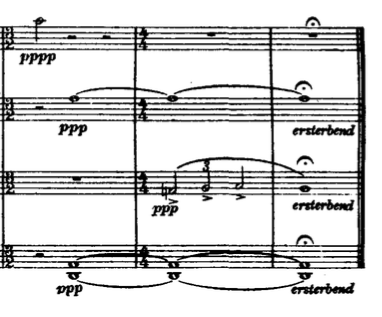

Mathew Fuerst, String Quartet No. 1 (opening):

“The work was written in collaboration with renowned German choreographer Marco Goecke. Marco gave me free reign to write whatever I wished to write, which at first seemed amazing. However, I soon found the project difficult, in part because of Marco’s wonderfully idiomatic choreography. I ended up spending hours watching and re-watching his work, hoping to write music that I thought would match the energy and intensity of his choreography.

“I had started and thrown out many sketches, and nearly finished one string quartet. However, I was dissatisfied with what I had written, feeling that the quartet did not compliment Marco’s choreography. With six days before I had to finish the commission, I restarted the quartet, and thankfully got the piece done in time.

“The piece is essentially in Sonata Form and contains music that is very aggressive, which I thought would compliment some of the wonderfully jagged choreography I observed in Marco’s work. Some of the material is borrowed from the violin writing of my Sonata-Fantasie No. 1 for violin and piano:

LISTEN: Mathew Fuerst, Sonata-Fantasie No. 1 for Violin and Piano (excerpt)

“Interestingly, after completing the quartet I discovered that the opening rhythm was being sung underneath my window by a bird. The rhythms were written into the work unintentionally and subconsciously!

LISTEN: Mathew Fuerst, String Quartet No. 1 (opening)

“To contrast the aggressive opening, I composed a more lyrical idea, which was the one thing Marco requested. This material actually developed some ideas that were written in earlier versions of the string quartet:

LISTEN: Mathew Fuerst, String Quartet No. 1 (lyrical theme)

“Those ideas would later be reused in the second movement of my Violin Sonata No. 3 since this music was material that my wife loved (the second movement was the processional at our wedding).

LISTEN: Mathew Fuerst, Violin Sonata No. 3 (2nd mvt.)

“The collaboration, For Sasha, was premiered in October, 2010 by members of the New York City Ballet and musicians from the American Contemporary Music Ensemble (ACME). The work lasts approximately 9 minutes.”

* * *

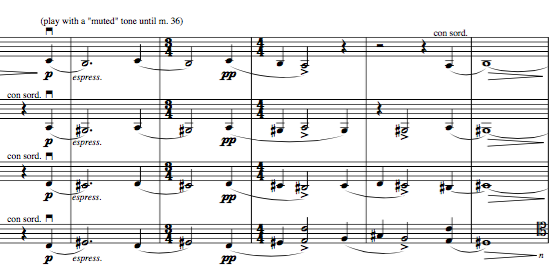

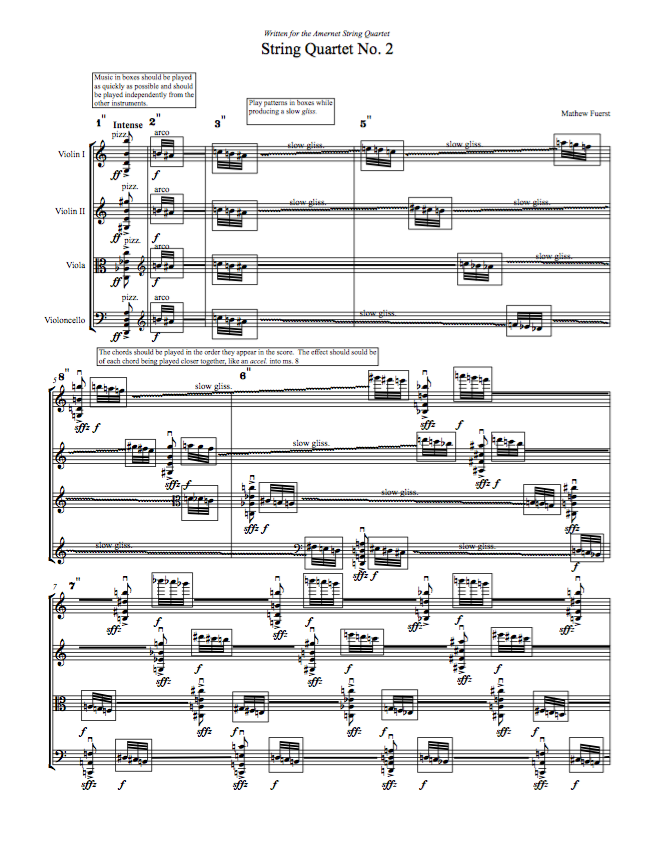

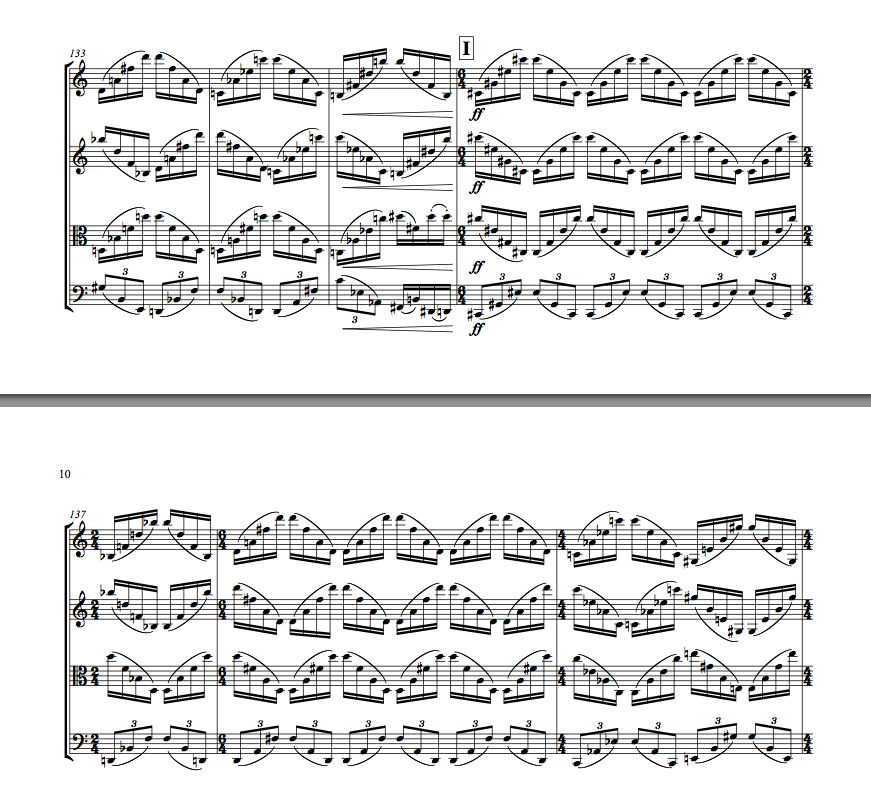

Mathew Fuerst, String Quartet No. 2 (opening):

“My Second String Quartet was written in the summer and fall of 2012 for the Amernet Quartet and premiered at Hillsdale College (where I teach) in the spring of 2013. While writing this quartet, I was reading a number of books on astronomy and parallel universes, and wanted to express my interest in this (particularly the Big Bang and the expansion that happened shortly thereafter). The quartet falls into three short sections. It is in the form of a chaconne for the first two sections. The first is my attempt to musically illustrate the Big Bang and the events that quickly followed. As the instruments start to expand from the B/A-sharp trill, chords start to appear (illustrating the creation of particles and mass), gradually getting faster until chaos is achieved. The chaconne is expressed through boxed notation so that the actual progression is virtually impossible to hear.

“The second section begins with artificial harmonics as the chaconne begins to reveal itself through canonic devices. At the climax, all the instruments come together to clearly play the 12-chord chaconne before breaking apart and presenting the first section in retrograde. The inspiration for this came from the theory of a Big Crunch, that the fate of the universe will collapse back into a singularity that started at the Big Bang. This was chosen for musical purposes more than anything else.

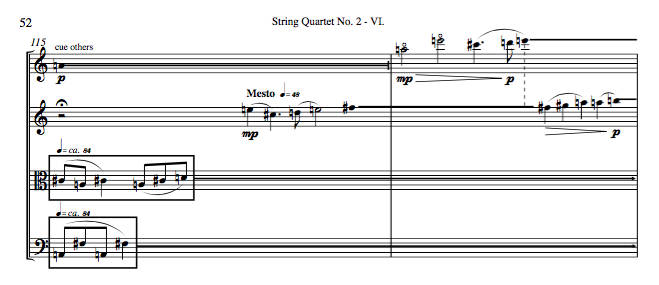

Mathew Fuerst, String Quartet No. 2 (beginning of second section):

Mathew Fuerst, String Quartet No. 2 (climax):

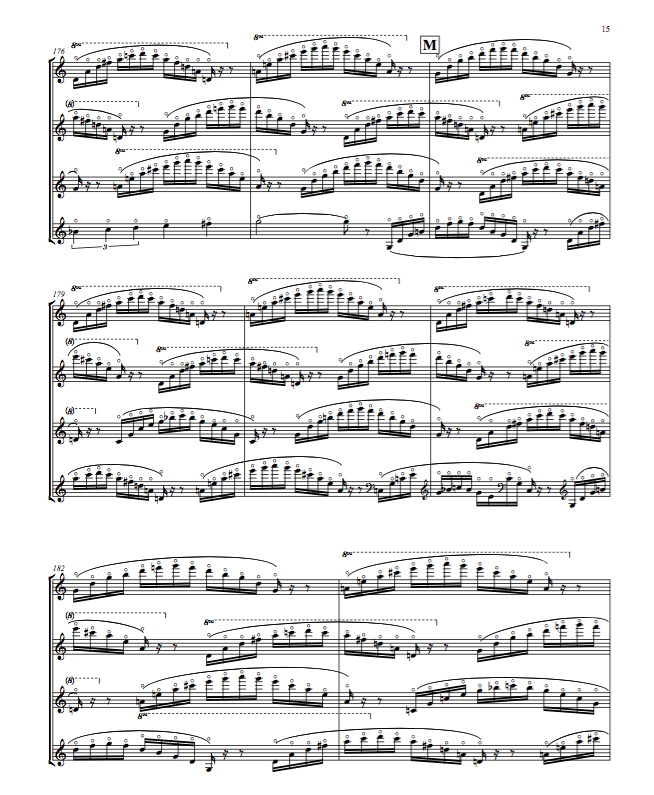

“The final section breaks away completely from the chaconne and is written using exclusively natural harmonics in order to create a mysterious ending. The work lasts approximately 9 minutes.”

Mathew Fuerst, String Quartet No. 2 (closing section, excerpt):

* * *

Alex’s quartet receives its world premiere on this program. Here’s what he has to say about that:

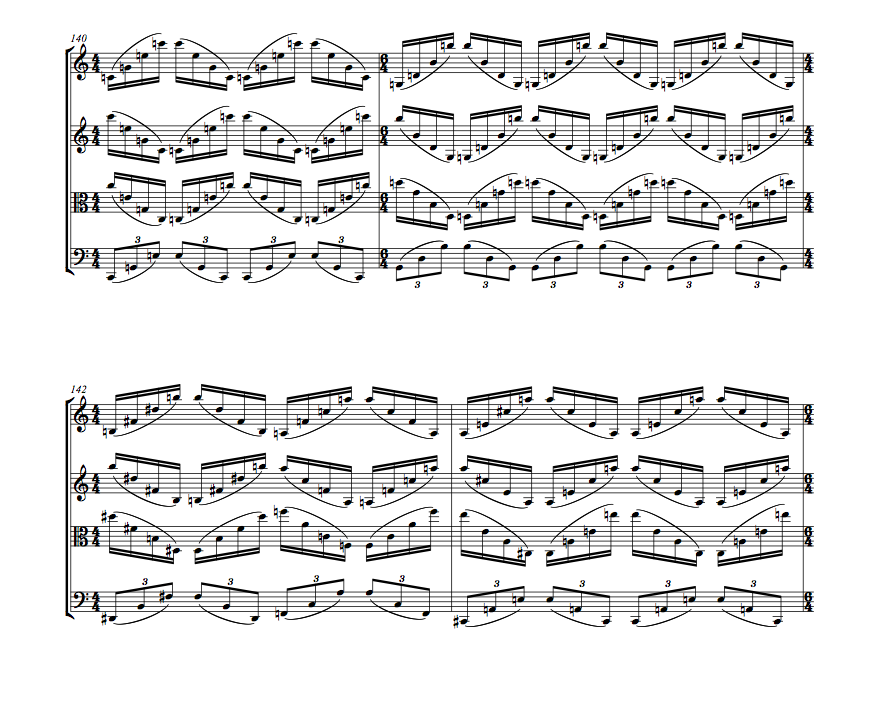

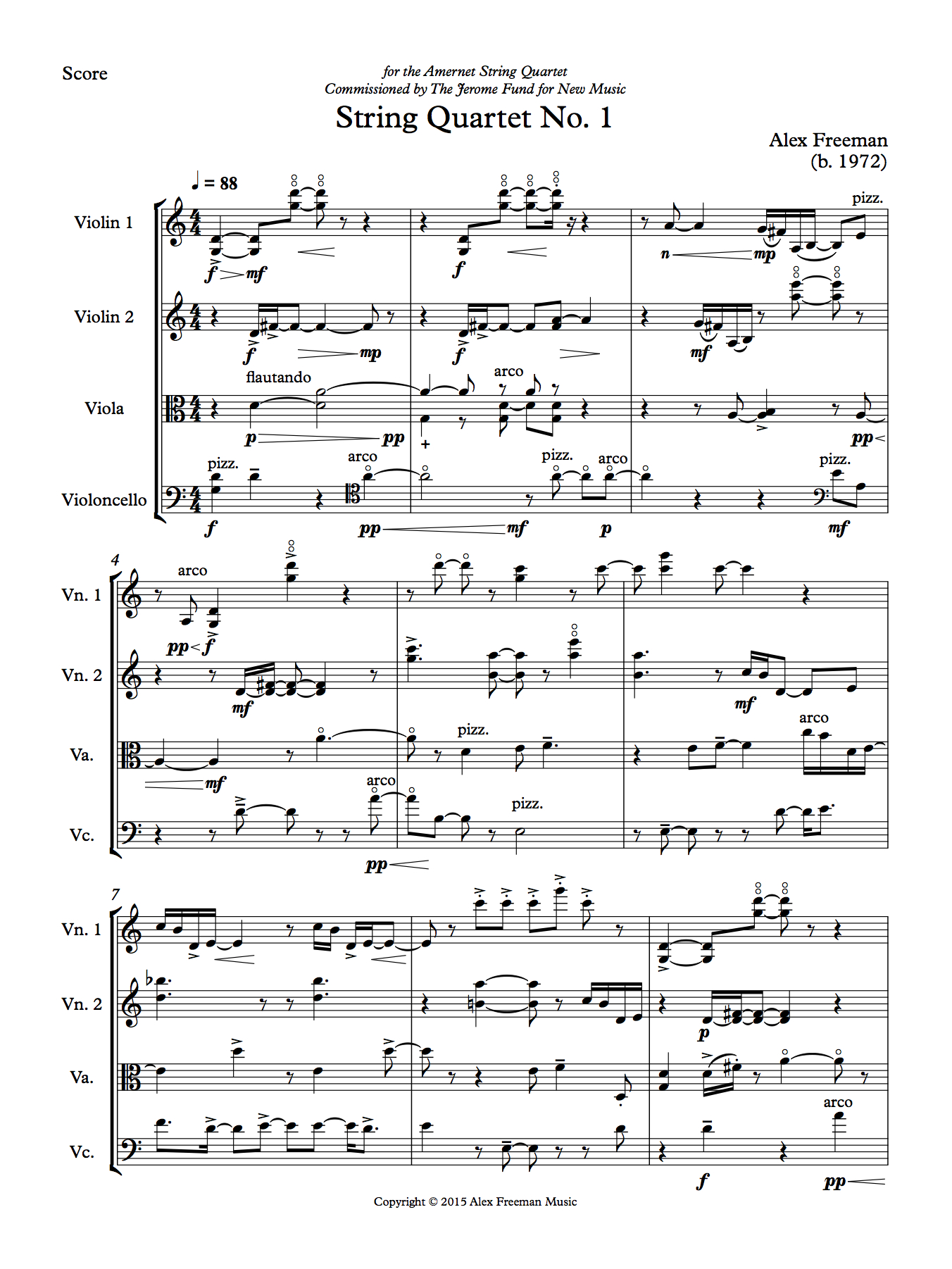

Alex Freeman, String Quartet No. 1 (opening):

“When I started String Quartet No. 1, I had envisioned a piece with a lot of tiered motivic events like this one:

“And it was inspired somewhat by a geologist friend showing me en échelon veins in rock formations:

“I also noticed that at least one visual artist was inspired by this, but I only found this late in the game. I include it here, because I think it is a nice visualization of what, for me, inspired a musical impulse in those rock formations:

“Honestly, I can’t remember which came first, but I had this motive in an array of tight canons in the early phases of the piece and thought it might be a good guiding concept and a cool-sounding title.

“You hear the motive a lot in the piece, but I didn’t end up making tiered entrances of it such an important aspect that I thought it really warranted my original subtitle, En Échelon, so I went with a simple catalog title, String Quartet No. 1. But it might be interesting to hear if, when you hear it, you think that title might make sense. I suppose there’s just as little “harp music” in Beethoven’s op. 74 as there are en échelon-style tiered events in this piece, so I may consider re-attaching the subtitle. I’d be really interested in hearing opinions on that from audience members after the performance!

“This piece was also intended to eschew extreme virtuosity to make it a work in my catalogue that might travel a little more than, say, my piano sonatas, which are feats of strength and endurance. So I intended to stay strictly within the 12-14 minutes our JFund commission proposal indicated and to try to make as much of it sound harder than it actually is—while still remaining within the realm of something a non-professional quartet could reasonably take on—as possible. It will be a learning experience working with the quartet and finding out where I might further tweak technical things in this piece. If you are a composer, especially a student, I would be more than happy to share any revisions I make after this premiere alongside the original version, to shed light on what adjustments were made. As a non-string player, I think there is an infinite amount to learn and I am quite sure there will be a riff or two that can be made technically less demanding with a minor tweak. I’ll be thinking about the technical difficulty level a lot when I hear the work.

“I will also be paying close attention to the relatively compressed form of this work next week when we hear the premiere. I tend to think in longer statements than this piece (it turns out that 18-22 minute statements are kind of my thing), so I am charting some new territory of concision here and I am hoping it breathes enough.”

* * *

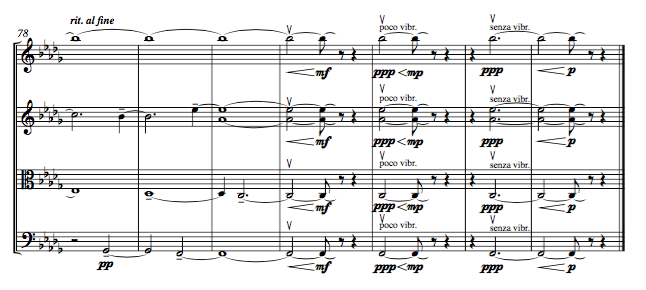

And now, here’s a little about my String Quartet No. 2:

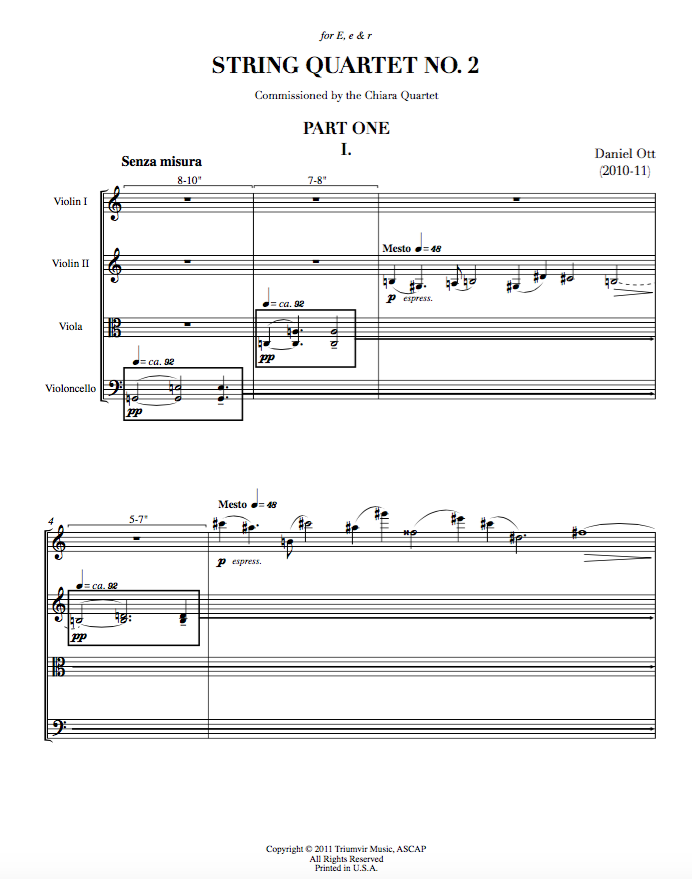

Daniel Ott, String Quartet No. 2 (opening):

Since I’ve already written a full program note for this quartet elsewhere on this site, I am going to try to stick strictly with a few musical excerpts of a more technical nature.

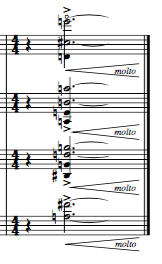

First off, the opening above has two main components: 1) The “white-note” chords in the boxes (made from 6ths—there’s no chord that’s easier to play on the strings, and I was going for a really easy, rolling kind of backdrop, almost like wind chimes); and 2) The “tune,” which is first in the 2nd Violin, then the 1st. I remember wanting the tune to go against the harmony a bit—it’s supposed to be melancholic—and the sharps make that mild bi-tonal effect. I also remember the 1st Violin entrance being exactly like the 2nd, just transposed up a step. But then there was a voice in my head that said, “Really? You’re really going to repeat that just in a different key? You can’t vary it at ALL?” So I displaced some of the intervals an octave lower, and stretched it out to make a more arcing line. It has an even more acerbic bite. As for those wind chimes, the boxes are used to make them rhythmically independent. But on top of that, each figure has it’s own note-value pattern. The idea with this kind of notation is to try to ensure that the players don’t line up. Even if they start a boxed pattern together, their independent rhythms will make them drift apart.

I’m big into recycling, musical and otherwise. (Just ask my wife—on recycling day I always end up re-doing our neighbors’ recycling so that it’s properly sorted!) So I tend to re-use or re-fit tunes in lots of different guises. Here are a few ways that the opening melody is transformed in the short first movement:

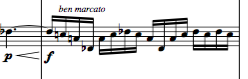

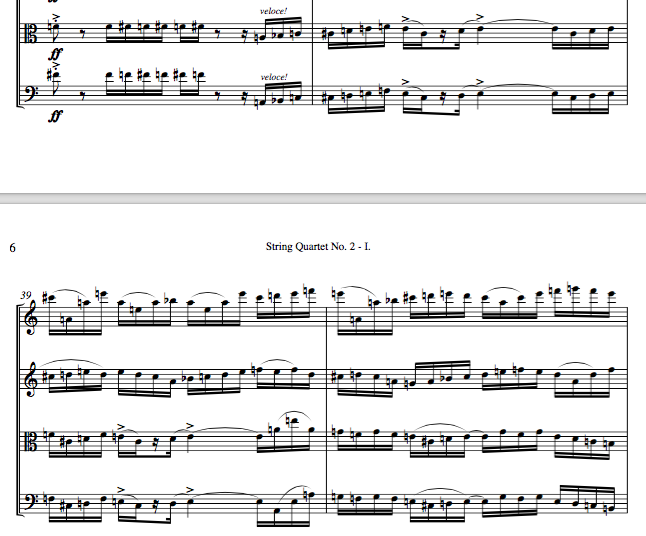

Same tune transformed as Allegro theme in Viola:

Here it is again, closer to original version, in Viola and Cello (marked “veloce!”):

And finally, made more lyrical than ever in Violin I and Viola (probably my favorite moment in the movement):

This work employs some quotes from other composers’ pieces. The first comes in the second movement, which is dedicated to the memory of Franz Liszt’s son, Daniel, who died as a young man. In response to that tragedy, Liszt composed a seldom-heard work called Les Morts. His piece is in E minor, so I used the same key signature in this movement (only two of the six movements have key signatures). Basically, the entire movement consists of repetitions of the falling half-step motive (known in music history as the “sigh” motive). My choice in using it was based on the fact that it’s what Liszt himself used in Les Morts.

Here’s the spot in the strings that I quote from the Liszt original:

There are some other quotes in the fifth movement of my quartet (most of them very much veiled) which all come from Mahler. The one I really hoped the players would pick up on is pretty subtle. It comes from Mahler 9, in the very last bars in the Violas.

Here it is in that piece, in glorious D-flat major (in the strings):

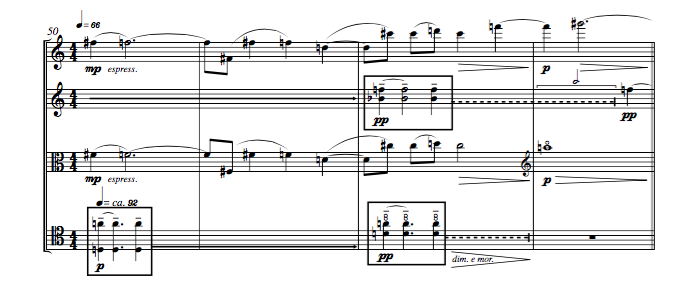

And here it is in my quartet (also in D-flat), not quite at the end of the fifth movement, but very close to it:

Originally, I had the ending of my “Mahler movement” sliding down the scale in each voice to a big, juicy D-flat major chord, just like Mahler did. But as I listened to it, I wondered whether that was too easy. Instead (and this is something I’m still really proud of), I “stopped short” of the long, slow descent to D-flat, and sort of froze on a chord here, where it gasps three times:

This chord is heard throughout the movement several times. The funny thing is, you’d think I’d planned it all along to end this way, but I didn’t! And this is the really fascinating thing about composing—sometimes your plans are interrupted or else change unexpectedly.

Since my piece is around 30 minutes long, I wanted to create a cyclical effect for the listener: Things from the beginning come back at the end, albeit often transformed. Remember the violin “tune” from the top? Well, the final movement returns to it just before the end, but now, rather than being dissonant, it all goes together in harmony:

Even the very last chord is the same as the “last breaths” from the fifth movement, just with the notes re-stacked to sound more “major-y”:

And, well, there you have it! A little guided tour of what goes on inside the composer’s workshop. If you’d like to hear all the stuff I illustrate in these examples, the entire piece is available to listen to in the MUSIC section of this website. However, I really hope that you’ll come here the piece live as well!!

My thanks to Matt, Alex, and the Amernets—I really think this is going to be a great concert, and I am very much looking forward to sharing it!

†Actual times may vary.